The UK government’s decision to reduce its foreign aid budget to 0.3% of gross national income (GNI) from 2027 marks one of the most significant shifts in its international development strategy in decades. While officials argue that the UK will remain engaged in global health, experts warn that such cuts will close lifesaving programmes, lead to preventable deaths, and undermine decades of progress in disease control.

The Scale of Reductions

For years, the UK was seen as a leader in international development, contributing 0.7% of GNI to aid projects worldwide. That figure fell to 0.5% in 2021, leaving many programmes struggling. A further cut to 0.3% represents a 40% reduction compared with pre-pandemic levels. Countries that have long depended on UK assistance—including Nigeria, Uganda, Nepal, Afghanistan, and South Sudan—are likely to face the greatest loss, just as they continue battling poverty, conflict, and fragile health systems.

Multilateral Health Initiatives at Risk

The UK has historically been a top donor to global health organisations such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the World Health Organization, and UNICEF. These contributions have saved millions of lives, but future support is now uncertain.

For instance, the UK recently pledged £400 million less to Gavi for 2026–2030. Analysts estimate this gap could mean 23 million fewer children vaccinated against diseases such as malaria and rabies, resulting in an additional 365,000 deaths over five years. If funding to a priority programme like Gavi is falling, other health areas may face even harsher reductions.

The Global Fund, which previously received £1 billion from the UK, is also vulnerable. Research suggests that every £10 million cut could cause 15,000 additional deaths, showing the severe impact of even modest reductions.

Polio Eradication at a Critical Stage

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative is especially fragile. The UK is its second-largest donor, committing £50 million annually until 2026. With polio still endemic in only two countries, eradication is within reach. But if funding falls, experts warn up to 200,000 children could face lifelong disability from the disease. Cutting support now would squander decades of global investment and risk resurgence.

Programme Closures Already Happening

The impact of budget reductions is visible today. The Fleming Fund, which focused on antimicrobial resistance in low and middle-income countries, shut down in 2025. The Global Surgery Unit, the world’s largest research project on surgical access in developing countries, may close by 2026.

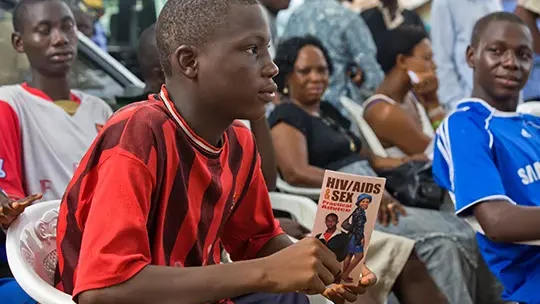

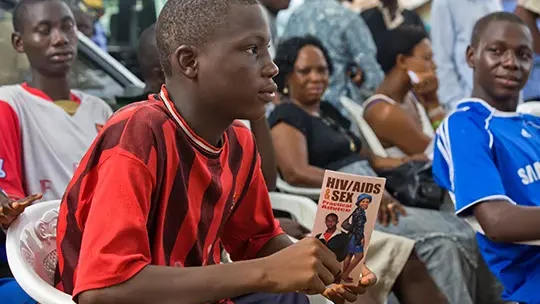

Women’s health initiatives face similar threats. The Women’s Integrated Sexual Health (WISH) programme, launched in 2018 to expand family planning in Africa and Asia, could see severe cuts. A 50% budget reduction would deny services to 1.7 million women and girls, leading to more than 800,000 unintended pregnancies and over 2,000 maternal deaths.

Africa Facing the Heaviest Burden

The Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office projects an overall 6% aid reduction for 2025–26, but for Africa the cut is double. This is alarming because African nations bear some of the world’s highest levels of extreme poverty and disease burden. Losing UK support could mean clinics running out of medicines, fewer vaccination campaigns, and more maternal and infant deaths.

Critics say this strategy contradicts the UK’s stated goal of creating “a world free from poverty on a liveable planet.” Without investment in health, poverty reduction will stall, and fragile economies will face deeper instability.

Wider Consequences for Global Security

Public health experts stress that cuts to international health aid are not only a humanitarian issue but also a risk to the UK itself. Infectious diseases can spread quickly across borders, and fragile health systems abroad raise the likelihood of outbreaks becoming global. COVID-19 demonstrated how quickly disease can disrupt economies and national security. By reducing investment now, the UK risks greater costs in the future if new epidemics emerge unchecked.

Conclusion

The planned UK aid cuts threaten to undermine decades of progress in global health. Reductions in contributions to Gavi, the Global Fund, polio eradication, and women’s health services could cause disease resurgence, maternal mortality, and preventable child deaths. Africa and other vulnerable regions stand to be hardest hit, but the consequences will ripple worldwide, threatening health security and economic stability.

Experts urge policymakers to reconsider the scale of reductions and recognise that foreign aid is not charity but an investment in global safety. Protecting health programmes abroad also safeguards the UK at home. The question remains whether the government will prioritise short-term savings or long-term human lives and global resilience.